New studies show that people suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder can find real relief with yoga.

When Sara talks about the benefits of practicing yoga, the 56-year-old from Boston uses the same terms as other yogis: being grounded and present, gaining an awareness of her body and its strength, feeling calm and in control of her thoughts. But as a victim of physical and sexual abuse who suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), Sara experiences these things a little differently.

For Sara—who asked that her real name not be used—being grounded literally means feeling her feet on the floor; being present means knowing where she is and what’s going on around her. These are things she can’t feel when she’s suddenly jerked into the past, reliving episodes of her ex-husband’s violence, like the night he chased her through the house and pushed through every door she hid behind.

“It can be very difficult to stay in your own body when you’re getting flashbacks,” she says. “The lighting changes, and you feel like you’re not even in the room.” Sara’s flashbacks come with little warning and can be triggered by anything that reminds her of the abuse.

This painful reliving of events is a common symptom of PTSD, a chronic anxiety disorder that can develop after someone is involved in a traumatic event, whether it’s a sexual or physical assault, a war, a natural disaster, or even a car accident. Existing treatments—which include group and individual therapy and drugs such as Prozac—work only for some patients.

Yoga can make a big difference, recent research suggests. In a study published last year in the Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, a prominent PTSD expert found that a group of female patients who completed eight hatha yoga classes showed significantly more improvement in symptoms—including the frequency of intrusive thoughts and the severity of jangled nerves—than a similar group that had eight sessions of group therapy. The study also reported that yoga can improve heart-rate variability, a key indicator of a person’s ability to calm herself.

“This is a really promising area that we need to examine,” says Rachel Yehuda, a professor of psychiatry at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine and the PTSD program director at the James J. Peters Veterans Affairs Medical Center in the Bronx. Soldiers returning from Iraq have high rates of PTSD and other mental health problems; one study reported the total at one in five. Veterans from other wars continue to suffer from PTSD—at times worsened by news from Iraq that reminds them of their own experiences.

The study’s most striking findings were patients’ own descriptions of how their lives changed, says the author, Bessel van der Kolk, a professor of psychiatry at the Boston University School of Medicine and medical director of the Trauma Center, a clinic and training facility in Brookline, Massachusetts. Van der Kolk, who has studied trauma since the 1970s, is considered a pioneer in the field.

“I’ve realized that I’m a very strong person,” says Sara, who continues to practice yoga. She says the slow but steady progress she’s made helps her face her ex-husband in court each time he violates a restraining order. By filing charges for every offense, she hopes to send the message that he can no longer be part of her life. “[Yoga] reminds me that if I just keep plodding along, I can get there,” she says. “I can face it in little chunks and say, “I can work with this piece.'”

Mind & body Connection

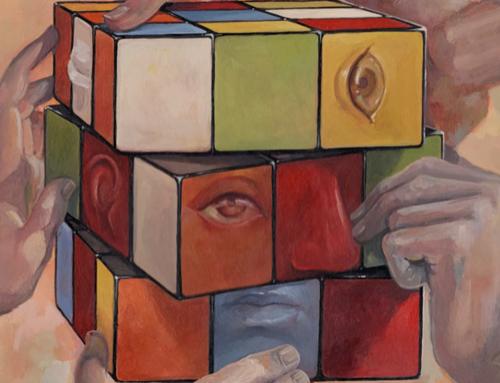

Van der Kolk first became interested in yoga several years ago, after he concluded that therapists treating psychological trauma need to work with the body as well as the mind. “The memory of the trauma is imprinted on the human organism,” he says. “I don’t think you can overcome it unless you learn to have a friendly relationship with your body.”

To learn more about yoga, van der Kolk decided to try it himself. He chose hatha yoga because the style is widely available, got hooked on it, and became convinced it could help his patients. “The big question became: How can you help people confront their internal sensations?” he says. “Yoga is one way you can do that.”

Van der Kolk found yoga a safe and gentle means of becoming reacquainted with the body. “Yoga reestablishes the sense of time,” he says. “You notice how things change and flow inside your body.” Learning relaxation and breathing techniques helps PTSD patients calm themselves down when they sense that a flashback or panic attack is coming. And yoga’s emphasis on self-acceptance is important for victims of sexual assault, many of whom hate their bodies.

To read the whole article please click here

Leave A Comment